Ryan Lovelace Is A Shaper From Santa Barbara. Any Questions?

He’s from Seattle, actually. But, still. It’s not easy to plant your planer into the boutiquey surf bubble that’s the Ranch to Rincon. You’ve got to be creative. You’ve got to be savvy. You’ve got to have a master plan. Lovelace, (29 in 2015), does not.

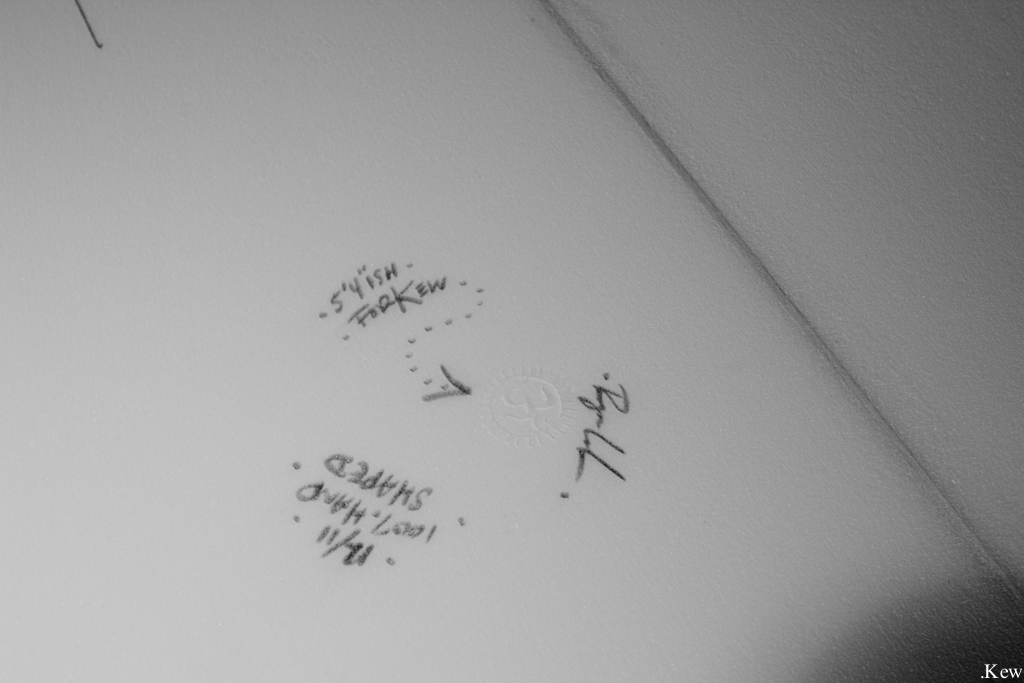

Photo: Kew.

A Dialogue by Michael Kew

[Originally published in Slide in 2011.]

So, what is this place?

[With a large pair of scissors, Lovelace is trimming fiberglass cloth around a freshly shaped 5’10” blank we’re standing aside.] It’s 132 Garden Street, the old Radon boatyard where they made all the urchin diving boats and shit. It’s been a part of the surfing and boat-building world in Santa Barbara since the late ‘60s, early ‘70s. There was a decently-sized label called Rippin Stix that made surfboards out of here back through the ‘80s and ‘90s. Afterwards, this little room got passed down through a couple different hands, including a ding-repair guy named Aaron, until I started sharing it with Damien Raquinio, a friend of mine. He had it for awhile. Then I got it, and I’ve been here for four or five years. It’s got some good energy, and as far as I can tell, that’s the reason it hasn’t or won’t be sold anytime soon. The ground is super toxic. The dirt’s all contaminated, and it’s only a block and a half from the main beach in Santa Barbara. Stearns Wharf is right there. In order to build on this property, you’d have to dig, like, 30 feet deep and remove and replace all the soil. I don’t think anybody really wants to do that.

What’s your rent?

I pay $144 a month for this, what, 9-by-11 room? The two rooms next door belong to a surf school [Santa Barbara Seals], but this whole building used to have surfboard-building stuff. There were three or four racks set up out there [points to the gravel street], and there’d be a bunch of dudes sanding boards. Dust just billowing out of the whole zone. I really wish I could’ve seen that. I want to do that. Well, not really. I guess I shouldn’t.

You feel a sense of history here. It’s womblike.

Definitely. Not so much as far as inspiring my work, but knowing that this has been a hub of small-scale Santa Barbara surfboard-building. It’s the last hideout. In this room, I’ve been able to learn pretty much everything I know about surfboards.

Where were you shaping before?

Damien and I had a room over on Mason Street, across from the Channel Islands retail store. It’s since been knocked down. We had to get out of there so they could crush it. Before that, I made boards in garages, on patios of apartments I rented.

When are you moving out of this room?

I’m supposed to be out of here in two weeks. It’s not going to be a surfboard-building spot anymore — it’s been shrinking since the old days. Now it’s going to be storage for the surf school.

You have a newer, larger shop gestating over by More Mesa.

Yeah, I just need to gather some money for the insurance, but I’ve been working on that place since December. It’s pretty much done. It’s an old greenhouse. From 1942 until 1995, it was a cut-rose operation for bouquets and stuff like that. It was 22 industrial greenhouses all connected to each other, so you could walk down the middle of them. My space is where they kept all the tools and stuff, but that building has been defunct since the mid-‘90s, so it’s falling apart. Broken windows everywhere, overgrown weeds. [Pours resin into a plastic mixing cup.] It’s pretty funky. So that place will be cool. It’ll be a change, for sure. That’s important.

What else is important to you?

Learning, but I don’t quite know what about. Sometimes I feel like I’m not learning interesting new things all the time because I’m so saturated by this. I’m not reading the news so much. I’m not involved in the latest politics. I’ve sunk into my little world of our friends and the surfing and the boards and everything. I don’t feel like I learn a lot, but, at the same time, I’m learning tons and tons and tons just about living as a fucking human being. [Laughs] That’s difficult enough. Just learning about myself and the way that I conduct myself, which is reflected in my surfboards, because my boards change whenever I do. [Picks around the room, looking for something.]

What are you looking for?

Extra cups. I scrounge for them because I don’t like wasting a bunch of new ones on what I know are just going to be shitty cups again.

How green of you.

I try. [Sarcastically] Well, I was raised in Washington, where they care about the environment. Naw, I do care about the environment, which is why the new shop is going to be awesome, because it’s a fair amount healthier than this boatyard.

So, who is Ryan Lovelace today?

Who am I? I guess [His cell phone rings, upbeat Indian music] I would characterize myself as someone with a pretty funny ring-tone on my phone. [Looks at it] A call from Verizon Wireless? I’ll call them back. So, who am I? I am a surfboard builder first. Wow, that’s weird. When asked who I am, I say I’m a surfboard builder before I say anything else. I guess that says a lot. I see myself as more of an artist than a surfboard builder every day, because I look at boards pretty differently when I think about what I’m trying to accomplish with each one. I guess we’re all trying to accomplish something. [Mixes a cup of blue pigment]

What designs are you into right now?

I’ve gone through hulls, kind of what people know me for. It’s funny because hulls are what I have loved for years, and I still do. I won’t ever dislike hulls. But there are other things I want to do when I surf. I’ve been on this trip for awhile lately that’s more based on the transitional period, meaning the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, which I guess would be characterized by McTavish and his vee bottoms and his work with Greenough. Unintentionally, I’m following the path of modern surfboard design in my own experiments, going from one thing to another and adding different things, but, in the same breath, my boards aren’t the same as anyone’s.

What separates them?

That’s a really hard question. [Mixing a cup of yellow pigment] If I was to try and look at it from a third-party viewpoint, I take old-school templates, do a lot of wide-point forward— [A foul odor forms]

Did you fart?

I did. And that’s just haunting, isn’t it? [Laughs] But, basically, I take the old lines that those guys were drawing, then take what we know about surfing and different styles that people have when they surf now, and I mix them in with those boards. So, modern foils and more modern rocker curves mixed with older templates. Modern curves in very non-modern shapes.

How are they modern?

I’ll use more high-performance rails. I’m not doing huge, boxy downrails or anything super turned up, or too much vee. Those guys back then used so much fucking vee, it was crazy. I’m using small vee panels, really light areas of vee in the board, not necessarily running off the tail. [Mixing a cup of blue pigment] Just using different areas of it and using what we know about it, what we’ve learned about it from the past 40 years, and making a more modern surfboard with it that’s not overdone. They were just trying anything back then. Boards would progress, and two weeks later they’d have something completely different, which was awesome. It’s what I tend to do now. They didn’t really sit down and pick apart each individual aspect — like make one exact board over and over again, with tiny adjustments to figure out what’s doing what. Those guys would do this, and it’d be radically different, then they’d do this, something else radically different. I’m able to look at what they did and apply what I know about surfboards now to those and make those kinds of shapes work like modern surfboards, not like old dogs. Not all the boards were dogs, of course, but you can watch old films and you can tell that they could bog pretty fucking hard.

So you’re 1967 meets 2011?

Pretty much.

But you generally avoid thrusters.

Every surfboard has its place. [Mixing a cup of green pigment] I’m not that curious about some boards because I don’t surf them that way. I don’t surf a thruster the way a thruster needs to be surfed, so I can’t really make them work that well. But I do have some customers who do, so I’ll make them a thruster, but it’s not going to be a really chippy thruster. [Pulls his latex gloves off, nods toward the unglassed board on the rack that we’re standing next to] It’s going to be like this thing. More nuggety.

Tell me about this board.

It’s a small version of the board that I’ve been obsessed with for the past four months, which, before I left for Australia, was a transitional-style board that came off of “Innermost Limits of Pure Fun.” I had this idea of what I wanted the surfboard to do just by watching that film and checking the templates out, studying frame grabs I’d take from when guys were walking down the beach. [Points out the door to Herbie, his brown daschund chihuahua] Check out Herbie — he’s all sleepy. Aw, little puppy. Um, so I was really into this certain idea of that one board that Kyle Lightner and I were looking at a few years ago. I was starting on that trend of thinking and ended up going to Australia after I shaped what I thought was my perfect board. I surfed a bunch with Jordan Nobel, who shaped Note Surfboards down there. He lives near and knows Wayne Lynch pretty well, so Wayne gave him an “Evolution”-style template. I rode the board that Jordan made from that template, which was a bit more modernized, had modern rails, thinner foil, and that thing was so fucking fun, even in bad waves. So I came back here pretty much knowing what I wanted my board to be. [Fills another cup with resin] I took the idea of his board, because I didn’t trace it while I was there, and what I remembered of it and made an 8-foot, wide-point back, rather hippy, with a really narrow round nose and a wide, round tail. An “Evolution”-style board, pretty much. When that film came out in 1969, surfing had progressed quite a bit [Dons a new pair of latex gloves to glass the 5’10”] from the “Innermost Limits” period. I find it funny that I went from following “Innermost Limits” to following the movies that came right after it, because my board design has kind of taken on the same line that they took. It’s cool because I’m like…well, it sucks because I look at it and I’m, like, “Sweet! Now I’m gonna do this, because this board works like that.” Then I realize and I’m, like, “Shit, these guys already did that.” [Laughs]

There is nothing new.

Never. Not at all. I guarantee that someone’s shaped a board like this somewhere before, but I feel like it’s new because it came into my head recently and I’m like, “Yeah-yeah-yeah!” And I have the fire for it, and I guess that’s how boards get revived. But all of the sudden, you realize somebody else did it.

What is this board?

[Grabs ventilator mask hanging from a nail in the wall] Okay, so, this board came down from the 8’0” that worked really well.

Name?

V-Bowls, which came from Kyle Albers’s board, D-Bowls, a longboard I was making last year. [Puts mask on, which muffles his voice, so he speaks louder] I rode that 8-footer and it was really, really fun, and I knew that that template was so balanced. Here, let me close the door real quick. [Closes the door to limit light so the resin doesn’t cure prematurely] That template was so clean and so balanced and so flowy that I knew that I could put it in any size board that I wanted to. Alter the foil and rocker a little bit to match the style of the fin set-up, and it would work. So I’ve been making them now. I’ve gone from 8’0” to 7’9” to 6’7” to 6’3”, and this one’s 5’10”. Each one looks like the same board, but they’re all going to surf very differently, depending on the fin template. I’ve made mostly single-fins; this one is a 2+1. I made a five-fin that’s super high-performance, full-on shortboard rocker and shortboard foil, and you look at that and you’re, like, “Wow! I haven’t seen one of these.” And then you say, “Oh, wait — Laser Zap.” Those boards Cheyne Horan rode in the ‘80s. This is just a refined version of that. So there is absolutely nothing new. Even though I wasn’t thinking about those boards at all after I drew it out, I was like, “Oh, I’ve seen that before.” It’s kind of defeating, but the boards still really differ when you get down to the small details. [Adds catalyst to resin, pours a small amount in a circle on the blank] I guess I’m talking more in generalities in terms of template and idea, the wide-point placement, but if you actually look at the fine details, this board is totally different — the concaves and the roll and the rails, the rocker, the fins. It’s got its own steez to it.

Tell me about your resin-dot logo. When we were in India, Craig Anderson called it the “best logo ever.”

Does he want to ride for me? [Laughs] A few years ago I made the first She Hull, and I was really stoked on it. Kyle Lightner and I were going to go take a bunch of pictures of it in the park at sunset, but I was rushing. I put a bunch of catalyst in the resin when I dropped the fin box [Adds catalyst to light blue pigment, pours onto blank] As you know, catalyst heats resin and makes it super hot. Well, I finished that board and set the resin cup down on the board, then left for about an hour. When I came back, I tried to pick the cup up but it had melted onto the board and delaminated a perfect circle on the bottom [Adds catalyst to dark blue pigment, pours onto blank] above and to the left of the fin box. I got really pissed off [Laughs] because now this board was screwed up with a huge delam on it, and I was supposed to take pictures of it right away. [Drags a yellow squeegee up and down the board, smearing the pigments together, excess resin drips to the floor] So I grinded off that section of the board and made a perfect white circle on the bottom of a dark blue board, and that board worked so well, it was ridiculous. It changed the way I thought about surfing and surfboards and my shaping, because suddenly I was making something out of pure inspiration instead of out of what I thought people would buy. That board really set the tone for how I made my boards, and since then, I’ve figured that some of the power of that board’s inspiration was in that circle somewhere. So I’ve made resin dots on every board since. [Refers to the board’s abstract pigment job] How’s this thing, dude? Pretty fucking sick! [Laughs] While I’m not even paying attention! Lost in my own thoughts and suddenly this thing happens. Fucking sick, dude. [Still laughing, dragging squeegee] Ultimate sea monster board.

Looks oceany.

Yeah, it does. I haven’t really made an oceany-looking board in awhile.

The top is going to be a solid color?

Yeah. I’ll probably use this dark blue. Or maybe that seafoamy teal. We’ll take a look at it from a distance when the bottom dries and see what’s up. So, basically, the resin dot was just a symbol of me following my passions instead of following what I thought the surfboard marketplace was dictating.

Which is what you’re grappling with.

Yeah, somehow, still. But I’m a lot closer because I haven’t cheapened myself and I haven’t made anything but what I want to make, and I’ve been decently successful. I’m trying to refine all of that. [Squeegees the cut lap around the rails and onto the deck] Taking what I’ve learned in the past year or two and simplifying it and not trying to make a big brand with all this shit. I don’t want to do a T-shirt line or anything — I just want surfboards, man. I just want to make fucking sweet surfboards. I do like T-shirts and I’m planning to make some, but not with the boards, not Point Concept shirts, not a brand.

Like your boards, you’re transitional.

Things always have been changing since day one of my boards, and every board is a little different from the last, and I don’t usually tend to copy an exact board, ever. I’ll do variations. I’m going to be between shops — I have been between shops for a few months now — but I’ll really be between shops if I don’t get this More Mesa shop figured out soon. I thought that I had to make a bunch of surfboards to make a living from it. Not full-on production, but just endless surfboards. I was trying to simplify it for myself when I was in Australia — to get some head space, asking myself about why I like doing this. I don’t make any money from it, really. Just barely scraping by for the last few years. I was trying to think why I put myself through it. I just really enjoy making boards for all my friends, and I can’t do that without selling boards to other people, so what I want to do is go back to focusing on custom boards. Still make shop boards, maybe, here and there for one or two shops. But I want to focus on developing different designs and if somebody wants to come to me and order a custom one, that’s fantastic. They always do. I get orders pretty constantly. But I want to consider myself as more of a freelance surfboard builder then a production builder. Not that I’ve considered myself to be a production builder before, but….

Why do you make surfboards?

I can’t really stop. I tried to a few years ago for a little while, but I couldn’t. I love surfing so much and I don’t feel like I could surf without building my own boards. [Finishes cut-lapping and rinses squeegee] It’s just too ingrained in my life, building stuff that I use is paramount to me. I grew up building all kinds of shit. I don’t really see doing it a different way. I have to feed my addictions. I like building surfboards as much as I like surfing them. [Removes latex gloves] I have to “go to work” and come to the shop, but I’m itching to get out here every day, literally.

Lovelace opens the graffitied shop door. Afternoon light floods the room and our eyes adjust. We step into the outside world and sit on a shaded piece of ground as the now-colorful board dries on the rack. Lovelace removes his shoes, finds a razorblade, and uses it to scrape dried green resin from his soles. Herbie the Dog sleeps on the cool pebbly dust beneath Lovelace’s car, a gray 2003 Honda Element that has three Point Concept Surfboards decals on the back of it.

Why are you shedding the Point Concept name?

When I started and was running Point Concept by myself, it was difficult to get stock boards into shops because most shops don’t buy them from you. They take them on consignment, especially when you’re a small-time guy. I needed some capital to get those boards out there, so I decided to take on some business partners. Over the year-and-a-half we were together, we had a difficult time meeting in the middle on how things should happen. They wanted to steer the business in ways that I didn’t want to go in order to chase profit margins — machine shaping and having other people finish the boards from there and outsourcing the glassing, too; T-shirt fashion lines and a large logistical structure for what was a very small operation. What I think they saw as freeing me from the labor of shaping and glassing, I saw as destroying what I wanted my life to be about. People stress communication for a reason, and, eventually, through months of disagreements and a whole lot of tension, the relationship failed. I left the company to them in July and went back to basics, because if I’m going to be making a shaper’s salary, I want to do it on my own with my pride intact.

What else have you been doing all summer?

Basically being homeless, living out of my car and sleeping on my girlfriend’s bed. I had to go through that phase of trying to make a larger business, a real brand, out of my surfboards to realize that that’s not what I want out of them. I don’t want that to be linked to my surfboards. They’re pure to me. They have an intention behind them and I feel close to them and I don’t want to build a business on the back of that. I want to keep it really fun. Obviously I do have to have some kind of business surrounding it to make sure I can keep doing it, but I don’t want to try and build a brand out of it, so I’m unbranding myself and refining my intentions and what I want out of this. Making the boards that I want to make and not be told that I have to do it one way because my brand says so, or that I have an image to uphold.

What’s your image?

I don’t know. I’m sure I get pigeonholed as some retro, groovy shaper, but my head’s been in it for so long now that I don’t see it as retro. It’s consumed my entire everyday life, and my life isn’t retro.

You don’t take a lot of measurements when you shape, do you?

I measure the length and width when I’m drawing out the template, and I’ll usually measure out the wide-point, or generally where I want the wide-point to be. If the curves changes it, that’s fine — I let the curve dictate what it wants to do. But I don’t really measure nose and tail dimensions. I don’t care about numbers too much aside from the very basic ones. I just want the curve to feel right and look right and have a natural flow and balance to it. I use my eyes to tell me if something is right or not. It’s more of a sensory experience and vision than it is a thinking game. I can brainstorm and think about a board, but it doesn’t really come to fruition until I put my hands on it. I had this board [Hooks a thumb back toward the drying board] in my head for the last week and a half.

I get really zoned-out when I shape. You can’t really talk when you’re shaping because the planer is so damn loud. I get in this weird zone and kind of meditate on it, and I didn’t realize that I do it till maybe a year ago. If I wear headphones and listen to music while I’m shaping, it’s a full-body high. It’s really intense.

What’s most important about a surfboard?

How it makes you feel. There’s the debate of form versus function, but it’s really all about how it makes you feel, because the form can be fantastic — you can stare it, look at the colors, lose yourself in it, and it’ll make you feel good because it’s your board — but you can get onto a wave and the color or look of the board doesn’t matter. Surfing is a very momentary, sensory experience. Everything is feeling. It’s nice to make pretty surfboards because I like the way that it makes you feel, and I like making surfboards that have a really sensible, purposeful form, because it also makes you feel real good when you surf it. So, putting the two together is the only way I want to make surfboards. I think a lot of people cut it short one way or the other, or they don’t tend to care about either one.

How so?

Some people just want to make a board that fucking shreds, and they don’t care what it looks like. That’s cool. I get that. A lot of times, that happens when I make boards for myself. Like, yeah, I don’t give a shit that that got smeared or this is weird, but still, with its imperfections, it’s perfect to me. There are guys who’ll make a clear board and just want it to shred well, and there’s guys who’ll make a really beautiful board and not quite understand what they’re doing in the form of it and the shape. They’re not making a functional board.

Are your boards functional?

You tell me, man. [Laughs] Fuck yeah. I wouldn’t make them if they weren’t functional. That’d be boring. I’d be an asshole shaper.