Cocody Rasta

By Michael H. Kew

MIDDAY, MIDWEEK, mid-August. Urban shantytowns—poverty, squalor, impromptu disorder. Clothes washed in brown rivers, draped to dry on roadside shrubbery. Broken glass and crushed beer cans. Scowls and rags. Twig fences and blank stares. Idle men and overworked women. Diesel-fumed, hazy air with a low gray sky that suffocates the earth. Endless roadside litter. A chaotic six-lane highway with older models of Mercedes and BMW swerving and speeding past ass-dragging taxis and crowded, top-heavy public buses.

West of Abidjan, civilization dissolves and the land opens. Verdant vistas and low hills, banana plantations, palm oil plantations, fields of maize and rice and passionfruit. Cassava, cocoa. Military checkpoints. People selling bottles of peanuts. Men pushing/pulling carts loaded with sticks. We’re inland, inside Walid’s Renault, blazing toward Liberia at 130 kph (80 mph) on Route de Dabou, the A3, a signed 70 kph-limit (40 mph) road that frequently slows us to a lurching crawl through its fields of wide, deep red-dirt potholes.

“Road is shit,” Walid says as he leans forward over the steering wheel, gripping it with his right hand, his left thumb and index finger to his lips, steadying a hand-rolled marijuana spliff, one of several today. “It’s not possible you dead from cannabis,” he says. “Not like alcohol. You can smoke kilo-kilo-kilo. It’s impossible you dead. Just smile.” (laughs)

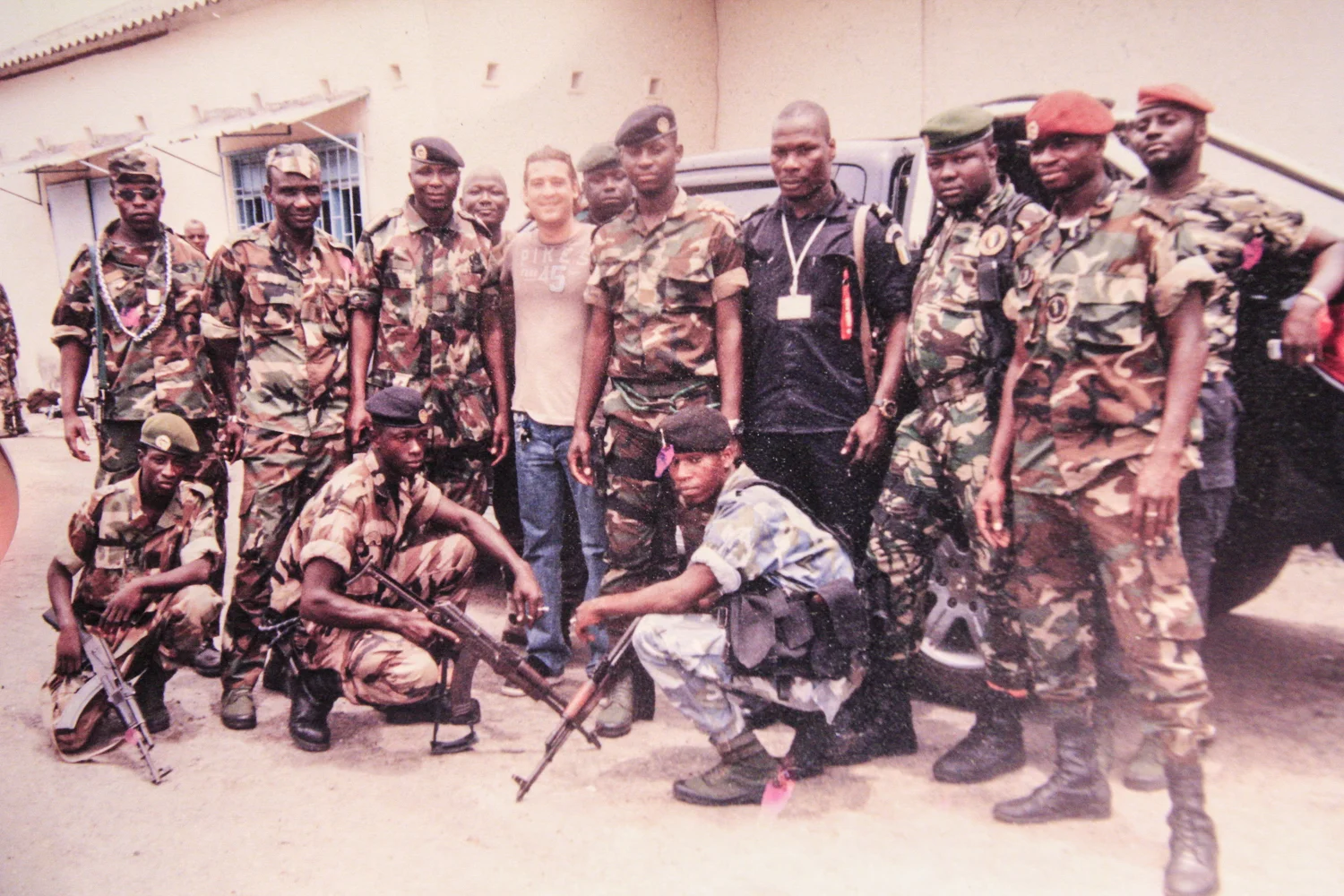

Sunglasses cover half his face and his right hand pilots us, the car shaking with the high speed, the horn getting a workout. Walid’s seatbelt is fastened only before entering the numerous military/police checkpoints, uniformed men with rifles and a thirst for bribery, pointing and shouting at our car to stop.

En route. Photo: Kew.

“Because of the war,” Walid says, exhaling pot smoke, “police just stop the big car, the big truck, for look, for control, but the white man is not stopped for bad. He stopped for just to take the money. But no control, you know? Just pay for take the road, give the money. Also give maybe food or water, a drink.”

Liberia, a nation too resurfacing from civil war and economic death, is at road’s end in the far west.

“Many-many-many Liberians come into Ivory Coast for the war, you know?” Walid says as we pass windswept fields of tall green grass and corn and manioc (cassava). “Mercenaries. They live here in the forest, in the jungle. On the frontier of Liberia and Ivory Coast, they have many army Ivorian, French army, USA army. The mercenaries go into Liberia and return to Ivory Coast village to kill many guys, to fuck many girls, take many riches. Mercenaries finish and return to Liberia.

“You have a big war for the frontier of Liberia and Ivory Coast. Liberian government and government Ivorian is working same for this problem. For three years, it not possible you come here on this road. It no possible. Oh, no. If you white guy come here? You finished.” (laughs) “You finished.”

“Police everywhere?” I ask.

“No police! Military, mercenary, Liberian, Angola, Sierra Leone—a mix. They don’t like the white man. Long time I don’t come here because of the war. Many problem. But it’s nice now for return. Africa is the future, you know? The future of the world. It no have development, it no have many this, you know? Africa is very beginning.”

At several areas along the road are machete-wielding men, hacking at tall green grass. Others are sitting or walking aside the vast fields of manioc and maize and rubber trees and palm-oil groves, the scenery stained with incongruous billboards hawking luxury cars.

The rain that threatened all day now begins to fall, smudging the red dust on Renault’s cracked windshield. The clouds mute the land and oppress the mud-hut villages we pass. The road is lined with fruit sellers, smoky fires, tall white rice bags of charcoal, naked kids, babies hanging off mothers’ backs, women with bundles of sticks atop their heads, broken trucks, brown lakes. People strolling in zen daze, time irrelevant. No other roads, just dirt tracks that blend into the weeds and woods.

“This road no good to drive at night,” Walid says, swerving to avoid potholes.

Soon he pulls over. We piss. The sun is sinking—orange hues on green. Back in the car, he rolls a joint while we listen to Alpha Blondy’s spirited Live Au Zénith, recorded in Paris in 1992. A multilinguist singer known as the Bob Marley of Africa, Blondy (birth name: Seydou Koné) was born in 1953 about 160 kilometers due north from where we sit. For me, an Alpha Blondy fan since the ‘90s, it’s fitting to hear his music in Côte d’Ivoire.

“This Alpha Blondy, he good, no?” Walid says after using his tongue tip to seal his new spliff. “You know Alpha Blondy in America?”

“Oh, yeah. I downloaded his new album (Mystic Power) before I flew here.”

“He very nice man. When I was child, he was my neighbor in Cocody.”

Among his vast discography, “Cocody Rock” is perhaps Blondy’s nexus. I know it well. Millions do, because Blondy’s reach is global, his message firm and up. In 2005 he was crowned Côte d’Ivoire’s United Nations Ambassador of Peace; later, he launched his Jah Glory Foundation, a non-profit, non-partisan charity. Ironically, his 2010 “peace and unity” concert in Bouaké (Côte d’Ivoire’s second-largest city and stronghold of rebels during the civil war) left two people dead and 20 injured.

“The workers let too many people into stadium at one time,” Walid remembers. He lights his spliff. “I was there. Very sad.” Inhales smoke. “So bad.”

Exhale.

So good.

We are the rockers from Zion Ivory Coast

We're ready, ready, ready, ready to rock, we're sayin'

Coco, Coco, is Cocody Rock

Coco, Coco, is Cocody Rasta

Photo: Kew.

Walid and spectator. Photo: Kew.