Crystal Tongue of the Aroma Garden

By Michael H. Kew

Flowers abound. Sweet, heavy scent of frangipani. Complex birdsong lifts from dense mango trees joined by sigh of surf and rush of rain.

Fresh baguette and two cups of coffee atop the black-sand beach fronting my pension, where I am the only guest. Crabs and herons forage in the damp reef flats. Two orange tabby kittens snooze by my feet. To the south: a loitering half-rainbow. Three shiny naked kids from next door frolic in a low-tide pool—one of many shallow holes I want the ocean to hide. This is Futuna’s leeward tip near the village of Toloke, which faces west-northwest. Oddly, this morning, the wind is onshore.

Two hundred yards out is a shelfy, boily right-hander spilling over a rough notch in the reef. With more tide, the wave might be rideable. Yesterday it did not exist. Today I notice what seems to be a small southwesterly groundswell.

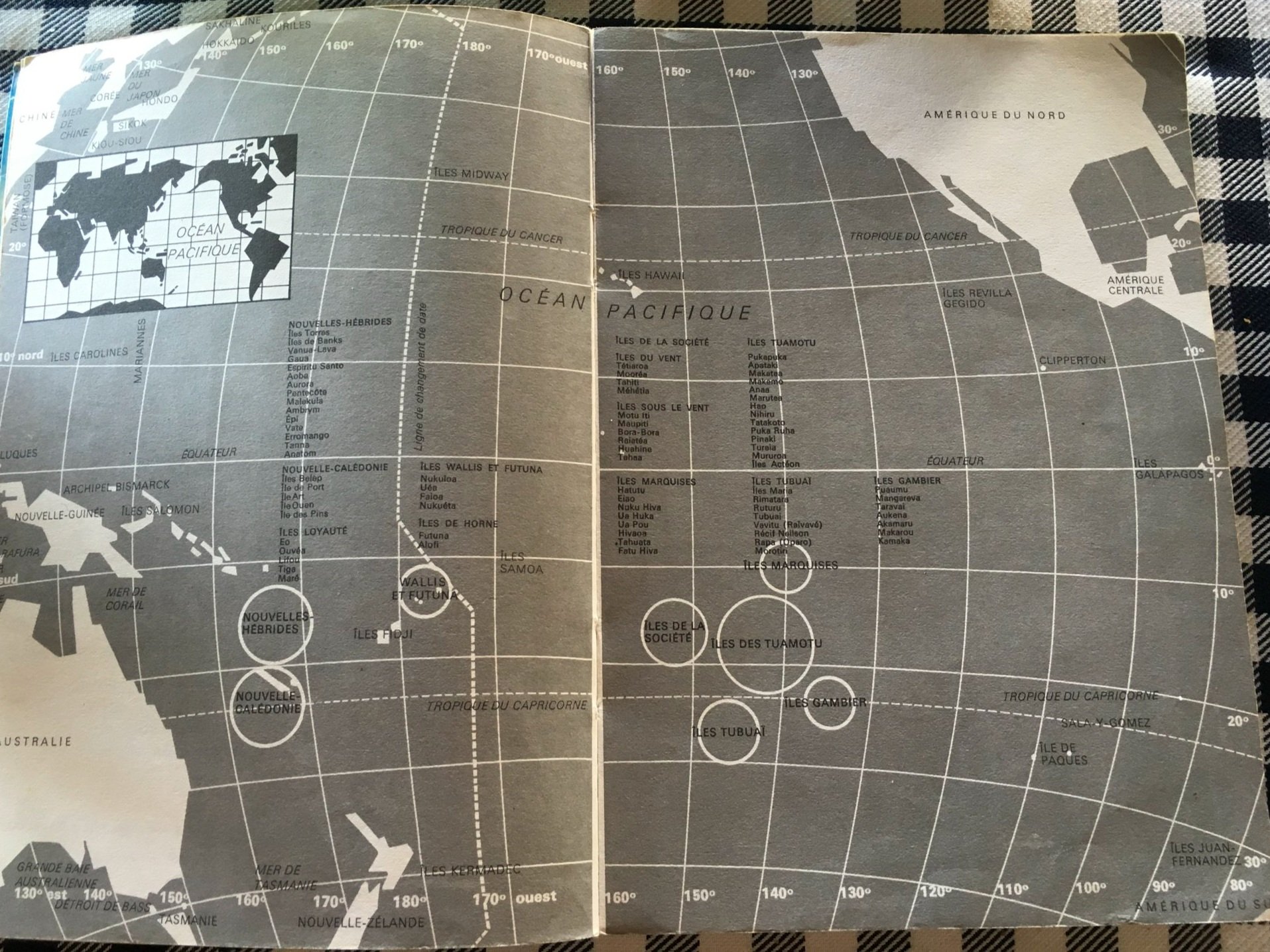

Killing time, I thumb through a mildewed 40-year-old softcover of Maurice Bitter’s Iles Merveilleuses du Pacifique, a volume you would only find in a place like the tiny foyer library here in Charles’s pension. The book is 160 text-heavy pages about the French Pacific—Nouvelle-Calédonie, Nouvelles-Hébrides (Vanuatu), Îles de la Société, Îles Marquises, Îles Gambier, Îles Tuamotu, Îles Australes, Île de Clipperton—yet just five are dedicated to Îles Wallis et Futuna. “Wallis Islands, end of the swell,” Bitter writes in French. “The loneliness. Rafts of greenery planted in the hollow of the long waves of the Pacific.”

Futuna is isolated from la Métropole—so isolated that, on February 22, 2016, François Hollande became the first French president to visit the island. (In 1979, President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing spent a whopping three hours on Wallis.) But Hollande only engaged the Kingdom of Alo, ignoring the Kingdom of Sigave, the western part of Futuna. Sigave chiefs were displeased and shunned the presidential stop for which 30 roasted swine were arranged in neat rows on grass in front of Hollande. Leis stacked to his ears, Hollande viewed the carcasses while he nodded and grinned and downed shells of kava. Dutifully, he was presented with the fattest pig.

With this global tour de France, Hollande fulfilled one of his 2012 campaign pledges: to visit all 11 French overseas territories, something no previous French head-of-state had ever tried to do.

“You met him?”

“Yes-yes-yes-yes, I met him,” Charles says, smiling as he refills my coffee. “Yes-yes. Everything!” He laughs at the memory. “He just coming for the morning and go back the afternoon. For six hour, he stay. Big ceremony for him in the rain.”

Hollande pledged an ATM and modern dialysis equipment since most Futunans were overweight and diabetic.

“Everything else he promised, he do,” Charles says, slowly, praisingly. “And the government has confirmed the president, so, maybe in three months, we will have an ATM here. The plane from Fiji—Fiji to Futuna? Yes, it’s okay. Futuna is closer than Wallis to Fiji. Next year, maybe we have a plane from Fiji direct. An ATR 42. Maybe Fiji Airways, eh?”

Later, swerving Charles’s car across another cratered piece of road, I decide that road repair funds would be more practical for residents, especially for those whom air travel is seldom (or never) a wish or a prospect. Futuna’s concrete thoroughfare is far worse than the isle’s dirt roads—driving on it physically hurts my back. The small Suzuki has five gears, but I never shift past third. A canine spay-and-neuter program would be handy, also, to curb the dozens of stray dogs that run amok, often narrowly missed by traffic. Lastly, some reef-blasting equipment for some prime new Futunan surf spots.

Facing the quaintly rotting village of Leava, Sigave Bay is small and murky, its entrance channel lined by a rough coral reef wide open to wind and swell. Few boats call at Futuna, which is why on this wet morning I am shocked to see a sloop moored inside of what looks to be a clean right-hander tubing off the top of the bay’s west reef. The tide is high, the ocean glassyblue, the waves brushed clean by the light offshores—gentle puffs, a zephyr from the northeast. A gift. The morning’s showery shifty clime had breached the normal July trades, baring an exceptionally rare surf window.

Sigave is a nook of storybook charm cusped by the infrastructural frugality of Leava (Futuna’s “capital”), tickled by a freshwater stream, all of it tucked beneath verdant forest that crowns 1,600 feet from sea level. Viewed while back-stroking along the reef’s edge, past the cluttered sloop, my mind awhirl with French words, belly of brioche and baguette, Futuna seems very much French Polynesian. But, divided by nearly 2,000 miles of ocean containing English-speaking nations (Niue, Tokelau, Tonga, the Samoas, the Cooks), la Métropole’s Polynesian flanks have little to nothing in common. Economically, geographically, politically, culturally, Futuna is an island unto an island, linked only to Tahiti via one syllable: France.

Unlike French Polynesia and la Métropole’s Melanesian territory of New Caledonia, Futuna has no surfy genetic code, no such chromosome. Which is why there is no chance of another surfer arriving to share with me these crystal-clear novelty waves, shallow and a bit dicey even at peak tide. As the tide ebbs, the Sigave right-handers stop—a spigot is spun shut, typical of such rawly capricious reef passes.

Past the reef, 250 yards from where I tread water, the depth increases sharply down the submarine mountain slopes, thousands of feet to the circum-Pacific seismic belt. Futuna and Alofi sit directly atop this fault zone, snug between the Pacific and Australian plates. Earthquakes are common—a small one hit two weeks before my visit—and Futuna exists with constant tsunami threat, particularly severe since nearly all 4,000 Futunans live along the island’s narrow coastal belt.

Heavy rain resumes. Another rainbow glows to the east, beautifully contrasted against the green land and gray clouds. Slowly I stroke shoreward, avoiding coral heads and urchins in the rapidly thinning water cushion. It is a 400-yard swim to the small black-sand pocket beach.

At 150 yards to go, a skinny, shirtless, middle-aged white man emerges from the sloop’s cabin, 50 yards to my right, mid-bay. He looks thickly bearded and sports a head of wild blond hair. He waves—Ça va!—and yells a sentence or two in fast French.

“Je ne parle pas français!” I reply, accidentally kicking the reef while huffing saltwater from my nose. “Parlez vous anglais?”

“Non! Australia?”

“États Unis! Touriste!”

“Me Nouvelle-Calédonie! Sailing!”

“Where?”

“Nouvelle-Calédonie! I sailing islands! Wallis et Samoa islands! Bora-Bora! Mo’orea! Tahiti! Two month Tahiti is good!” He grins large and points a thumb toward the darkening sky. Suddenly feeling exhausted, I smile and wave back to him before resuming my swim.

Back on land, in the fading light, I enjoy the rain’s cool rinse. Charles’s car is parked aside a medium-sized fale that holds a rack of plastic kayaks, likely used by fishermen, and three upturned wooden canoes. Next to them is a blue swing set poised for the sunny weekend laughter of children.

The rain stops and clouds part. Birds chirp in the soft pastel twilight. Two teenaged boys in NBA team jerseys, followed by a few fat, barefooted women in bright dress, walk past. I smile.

“Parlez vous anglais?”

No.

This is normal.

Akin to being invisible or inside a silent film. Unable to engage Futunans, I regret cheating and faking my way through three years of high-school French.

{Plucked from Rainbownesia, available globally via Amazon.}

{All images by Kew.}